The art of diabetes care: guidelines for a holistic approach to human and social factors

Article information

Abstract

A holistic approach to diabetes considers patient preferences, emotional health, living conditions, and other contextual factors, in addition to medication selection. Human and social factors influence treatment adherence and clinical outcomes. Social issues, cost of care, out-of-pocket expenses, pill burden (number and frequency), and injectable drugs such as insulin, can affect adherence. Clinicians can ask about these contextual factors when discussing treatment options with patients. Patients’ emotional health can also affect diabetes self-care. Social stressors such as family issues may impair self-care behaviors. Diabetes can also lead to emotional stress. Diabetes distress correlates with worse glycemic control and lower overall well-being. Patient-centered communication can build the foundation of a trusting relationship with the clinician. Respect for patient preferences and fears can build trust. Relevant communication skills include asking open-ended questions, expressing empathy, active listening, and exploring the patient’s perspective. Glycemic goals must be personalized based on frailty, the risk of hypoglycemia, and healthy life expectancy. Lifestyle counseling requires a nonjudgmental approach and tactfulness. The art of diabetes care rests on clinicians perceiving a patient’s emotional state. Tailoring the level of advice and diabetes targets based on a patient’s personal and contextual factors requires mindfulness by clinicians.

A holistic approach to diabetes

As a long-term illness affected by lifestyle, diabetes requires a holistic approach [1-3]. Holistic care in clinical medicine may be defined as a focus on overall health and well-being [4]. It is humane, compassionate, service-oriented, and relationship-based. Its vision encompasses clinical, human, and societal contexts. This high-level perspective is based on the contextual mindfulness of clinicians [5].

Context of the illness

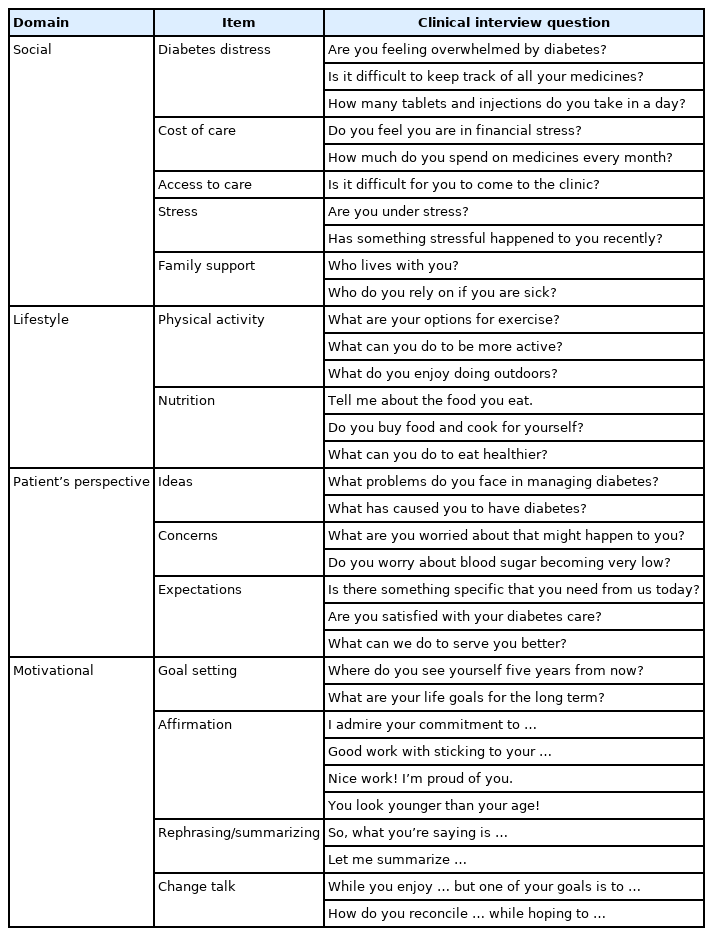

Factors such as health literacy, access to care, family support, and living conditions can influence diabetes outcomes [6]. Issues such as the availability of whole foods, home-cooked meals, and support from household members can affect nutrition [7]. Access to parks, safe walking paths, and clean neighborhoods supports an active lifestyle. Clinicians should ask about, document, and consider these nonmedical factors (social determinants of health) in treatment planning (Table 1). Children, women who are pregnant, ethnic minorities, those who are older, individuals with extreme obesity, rural residents, and those with comorbid mental health conditions require special consideration regarding these contextual factors [8,9].

Emotional health

Psychosocial stress due to family dysfunction and work pressure can profoundly impact diabetes. Patients experiencing stressors may experience difficulties following diabetes self-care instructions [10]. Diabetes can cause distress, which is the emotional stress associated with living with diabetes [11]. Emotional stress is important in patients with diabetes and should be considered in clinical care. Diabetes imposes a relentless burden of daily medications and dietary restrictions. Diabetes distress is more common in patients with type 1 diabetes and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes [12]. Higher diabetes distress correlates with worse glycemic control and lower overall well-being [13]. However, a normal glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level does not rule it out. Diabetes distress is more common than and can be confused with depression [14]. Increasing pill burden and frequent glucose monitoring worsen distress. Clinicians should explore patients’ feelings about living with diabetes.

Patient-centered communication

Patient-centered communication is the foundation of a trust-based relationship [15]. Core skills include eliciting the patient’s agenda and priorities, asking open-ended questions, active listening, responding with empathy and non-verbal gestures (concerned facial expression and head nodding), and exploring the patient’s perspective. The patient’s ideas about disease causation, concerns about the impact on daily living, and unexpressed expectations influence diabetes self-care.

Individuals with diabetes may fear its impact on their lives. Such fears include the risks of blindness, amputation, dialysis, and painful neuropathy. Initiating insulin injections is a common concern. Additionally, individuals may be worried about hypoglycemia, leading to loss of consciousness, social embarrassment, reduced mental acuity, and sudden death. They may hide these fears from health professionals because of reticence or concerns regarding restrictions on driving and independent living. It is important to alleviate a patient’s fears and concerns through patient-centered communication.

Cost burden

Physicians should be more mindful of the costs borne by patients and their healthcare systems. Overburdened care can lead to the discontinuation of essential interventions. The cumulative long-term burden can be prohibitive for many individuals [16,17]. As the diabetes care paradigm shifts from glycemic control to patient-oriented outcomes such as reducing macrovascular complications, medication selection needs to be more transparent. A thoughtful discussion on drug prices, co-pays, and the expected benefits of treatment can empower patients.

Frequent laboratory requests, such as HbA1c, electrolytes, and renal and liver function tests, may be burdensome without altering medical management. Excessive fingerstick glucose testing may be less useful in patients with stable type 2 diabetes receiving oral medication [18]. Simply informing patients about their HbA1c results, without discussing behavioral issues, does not seem to improve lifestyle choices [19]. Monitoring clinical parameters, such as blood pressure, waist circumference, vision (fundoscopy, visual acuity, and peripheral vision), and foot sensation, may be more useful in resource-constrained settings. Although less effective than an in-person interaction, follow-up via telephone can reduce the burden of clinic visits.

Glycemic goals

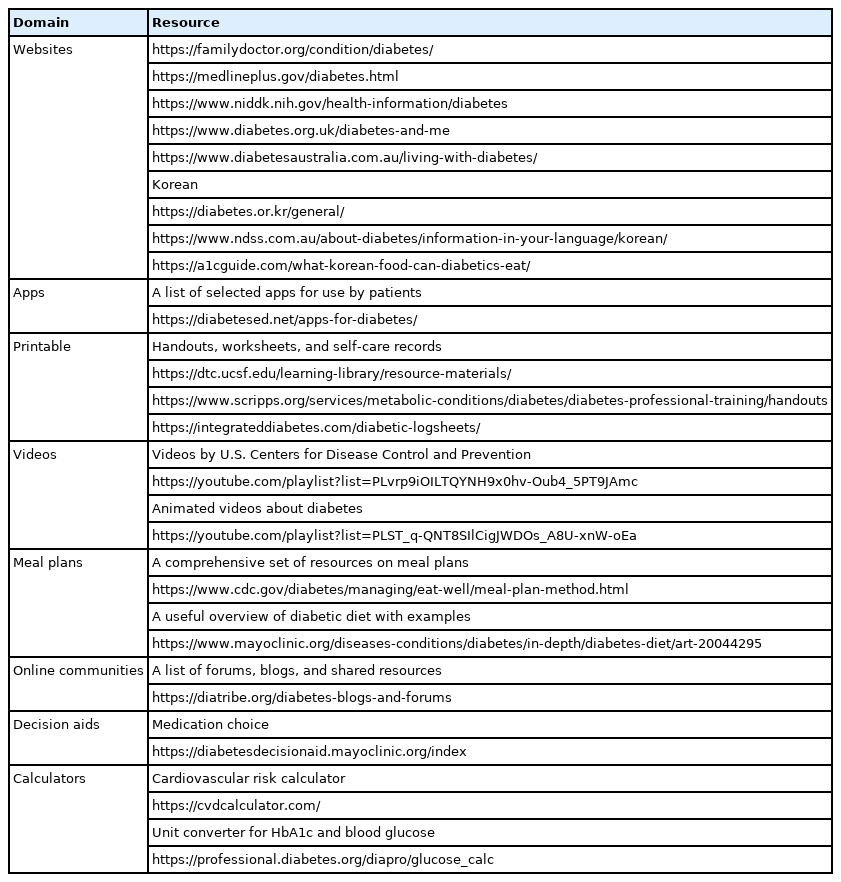

The target HbA1c level for many individuals must be tailored according to context. Factors such as frailty (but not necessarily age), the risk of hypoglycemia, support from household family members, and food security may need to be considered. An aggressive target may not be justifiable in an individual who is frail with a limited life expectancy. A high pill burden (number and frequency per day) can negatively affect patient morale and quality of life, sometimes leading to complete nonadherence. Patients should be asked about the burden of treatment (especially insulin). Insulin treatment may become inevitable; however, it requires the patient’s commitment to be safe and successful. Respect for a patient’s decision to defer insulin demonstrates epistemic humility on the part of the clinician and concern for personal autonomy. To achieve a reasonable chance of treatment adherence, the patient must feel in control. Open-ended questions (“Tell me more about your…”) shift the locus of control toward the patient (Table 1). Well-designed educational resources empower patients and enable richer conversations regarding diabetes goals (Table 2).

Lifestyle focus

Type 2 diabetes can be considered a lifestyle condition [20]. Despite widespread awareness, many patients are unable to adopt lifestyle recommendations [8,21]. Psychological, household, and societal obstacles form a frustrating structural barrier for these well-intentioned individuals [22]. The art of motivational interviewing lies in creating a nonthreatening space for patients to express their issues. The clinician’s role mimics that of a coach. Patients’ choices are not judged as good or bad but rather as congruent or in conflict with self-expressed goals. Mini-lectures on diet and exercise cannot be considered effective patient counseling. Simplistic advice disregards patients’ understanding of their complex social situations and dismisses their prior attempts at change. Clinicians should avoid assigning blame for poor disease outcomes on patients. In contrast, motivational interviewing uses non-directive techniques such as patient engagement, nonjudgmental listening, exploring ambivalence about behavioral change, encouraging patient-led goal setting, and evoking patient motivation to change. Instead of a series of dreaded reminders, the clinician engages in what appears to be friendly conversation. Not all clinic visits should include lifestyle counseling. Physicians should be mindful of the patient’s emotional state when handling conversations about change. Emotionally distressed patients may not be able to assimilate detailed instructions. In these situations, the physician takes a “backseat” and lets the patient express his/her ideas, fears, desires, and hopes. This awareness of the patient’s emotional state and social context is based on mindfulness of the clinician [23]. The art of diabetes care relies on reflective mindfulness.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.