Pathological interpretation of connective tissue disease-associated lung diseases

Article information

Abstract

Connective tissue diseases (CTDs) can affect all compartments of the lungs, including airways, alveoli, interstitium, vessels, and pleura. CTD-associated lung diseases (CTD-LDs) may present as diffuse lung disease or as focal lesions, and there is significant heterogeneity between the individual CTDs in their clinical and pathological manifestations. CTD-LDs may presage the clinical diagnosis a primary CTD, or it may develop in the context of an established CTD diagnosis. CTD-LDs reveal acute, chronic or mixed pattern of lung and pleural manifestations. Histopathological findings of diverse morphological changes can be present in CTD-LDs airway lesions (chronic bronchitis/bronchiolitis, follicular bronchiolitis, etc.), interstitial lung diseases (nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis, usual interstitial pneumonia, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, and organizing pneumonia), pleural changes (acute fibrinous or chronic fibrous pleuritis), and vascular changes (vasculitis, capillaritis, pulmonary hemorrhage, etc.). CTD patients can be exposed to various infectious diseases when taking immunosuppressive drugs. Histopathological patterns of CTD-LDs are generally nonspecific, and other diseases that can cause similar lesions in the lungs must be considered before the diagnosis of CTD-LDs. A multidisciplinary team involving pathologists, clinicians, and radiologists can adequately make a proper diagnosis of CTD-LDs.

Introduction

In patients with connective tissue disease-associated lung diseases (CTD-LDs), lung biopsies show fibro-inflammatory changes in various compartments of the lung, including the airways, alveolar walls, alveolar spaces, pleura, and vascular structure. CTD-LDs often reveal acute, subacute, and chronic fibro-inflammatory lesions within the same biopsy specimen, indicating an ongoing pathological process [1,2]. Most CTD–associated interstitial lung diseases (CTD-ILDs) show nonspecific microscopic patterns that are indiscernible from idiopathic interstitial pneumonias of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) or organizing pneumonia (OP) [1]. It is important to confirm the patient's underlying systemic disease before pathological interpretation and diagnosis of CTD-LDs [3,4]. CTD-LDs reveal certain histological patterns of ILD, and it is possible in many cases to make a diagnosis of CTD-ILD and give important information about patient management through surgical lung biopsy including video-assisted thoracoscopic biopsy [1].

Some histopathological changes in CTD-LDs are not direct manifestations induced by CTD on the lung, but can be induced by drug therapy or other systemic complications in patients with CTD. It is difficult to discriminate which findings are related to the patient’s CTD or secondary effects in the lungs on microscopic examination [3,5]. The case of CTD-LDs should be reviewed by a team of specialists, including pathologists, rheumatologists, pulmonologists, and radiologists, for accurate diagnosis and confirmation of underlying etiology. This article will cover the pathological interpretation and diagnosis of the pulmonary changes seen in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic sclerosis (SyS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), polymyositis and dermatomyositis (PM-DM), Sjögren syndrome (SjS), and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD).

Histopathological pulmonary patterns in rheumatoid arthritis

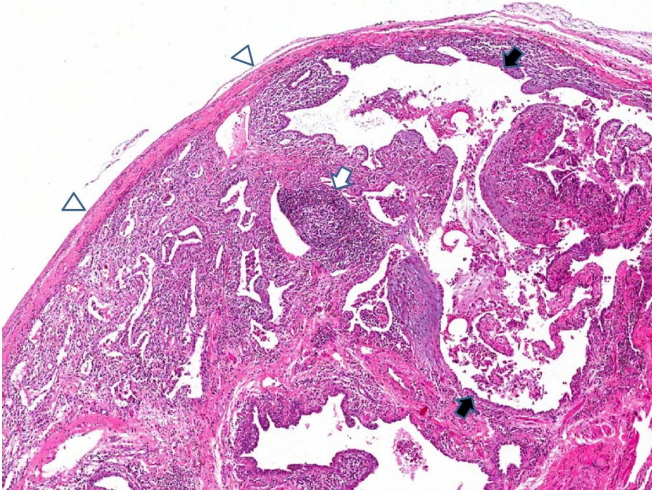

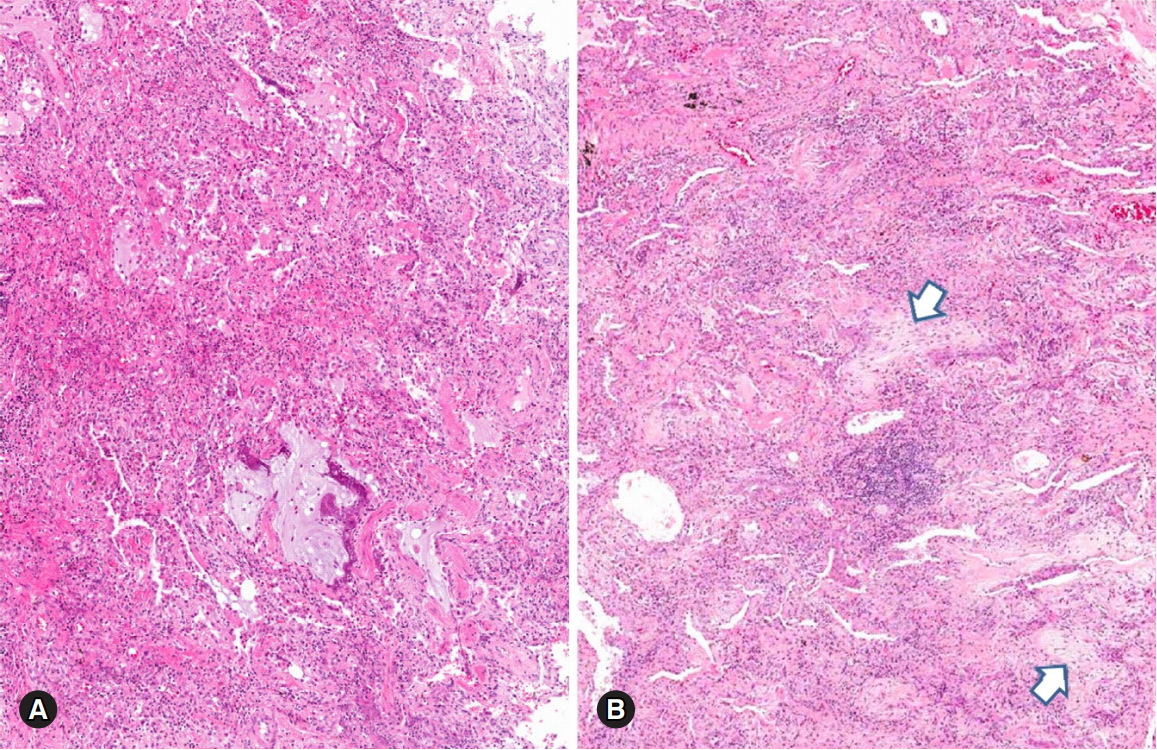

RA associated with lung diseases can affect all anatomical areas of the lungs, including airways, alveoli, interstitium, vessels, and pleura [1]. Common pleural manifestations of RA are pleural effusion, acute fibrinous pleuritis, chronic fibrous pleuritis, and pleural adhesions [1,6,7] (Fig. 1). RA reveals single or multiple nodular lesions in the pleura, interlobular or alveolar septa, and the rheumatoid nodules are considered the most diagnostic finding of RA-ILD. Pathologically, rheumatoid nodules measure up to 2 to 3 cm and consist of a central portion of eosinophilic necrosis, occasionally neutrophils, that is surrounded by appearance of epithelioid histiocytes and scattered giant cells [1,6,8]. The most common histological pattern of RA-ILD is NSIP (30–67%), followed by UIP (13–57%) [1-3,9,10].

Chronic fibrous pleuritis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Pleural adhesion (black arrows), fibrotic interstitial pneumonitis (asterisks) and focally lymphoid aggregates (white arrow) are present (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40).

The microscopic features of RA-NSIP or RA-UIP mimic those seen in idiopathic NSIP and UIP. More prominent interstitial lymphocyte aggregates and/or occasional germinal centers can be seen in the alveolar walls or peribronchiolar areas in RA-UIP [1,8] (Fig. 2). In contrast, fibroblast foci are more characteristic findings in idiopathic UIP rather than RA-UIP [3,11]. Histological patterns of inflammatory airway diseases, such as bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, or follicular bronchiolitis can be present in the RA-NSIP or RA-UIP [10,12]. Acute and subacute inflammatory lung lesions including DAD and OP are often seen in RA-ILD with an acute exacerbation, or initial pulmonary lesions of RA [6,13,14]. Acute vascular manifestations including vasculitis, capillaritis or pulmonary hemorrhage, and chronic vascular manifestations are rare in RA-ILD [15].

Histopathological pulmonary patterns in systemic sclerosis

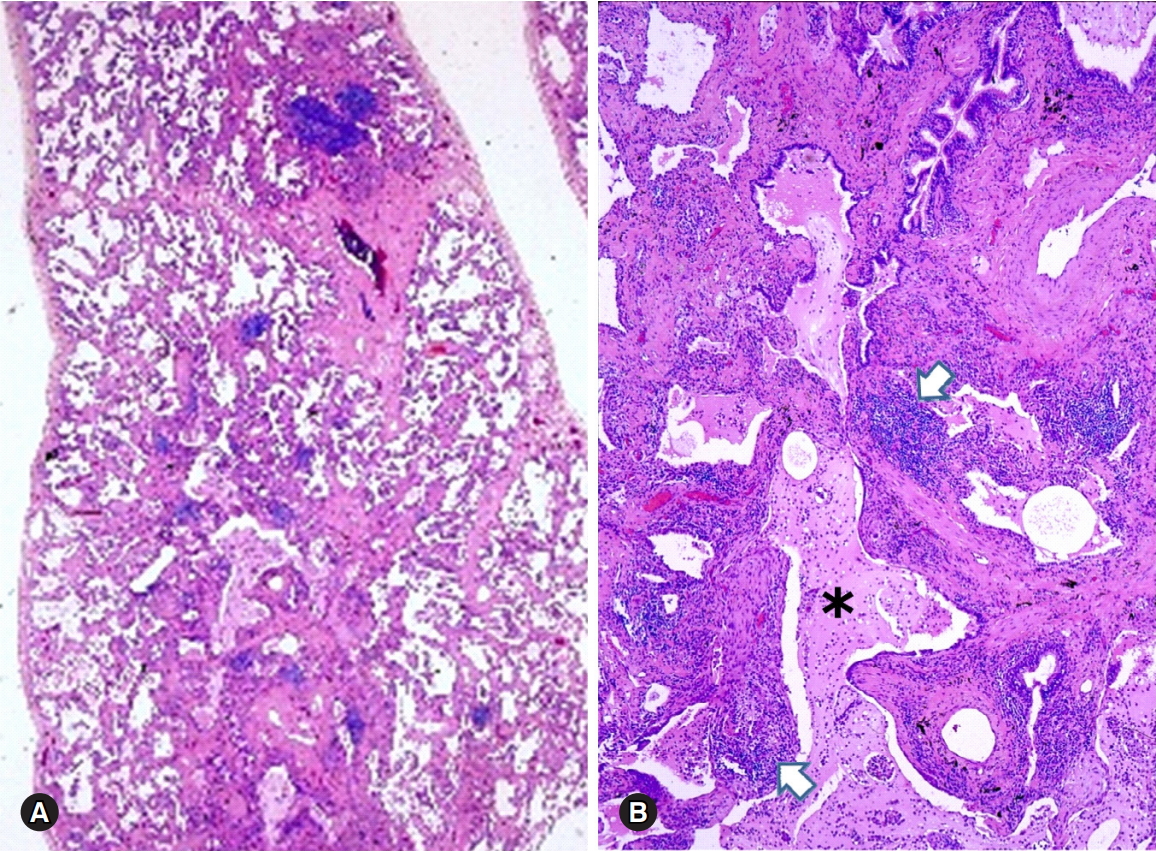

ILD occurs in up to 80% of SyS patients, and ILD is the most characteristic finding in SyS than in any other CTD [1]. The major histological features of SyS-ILD are collagenous interstitial fibrosis and hypertensive vascular changes [16]. The characteristic findings of SyS-ILD are fibrotic NSIP with paucicellular and collagen-rich interstitial fibrosis, maintaining the lung architecture and often preserving the subpleural area [1,17] (Fig. 3).

Fibrotic NSIP in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Diffuse fibrotic interstitial thickening with NSIP pattern and relatively sparing the subpleural area (A, arrows heads). The thickened interstitium shows paucicellular and collagenous fibrosis (B, arrows) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×10 [A] and ×200 [B]). NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

When lung lesions progress, the fibrotic changes becomes confluent and this leads to honeycombing or end-stage lung [1]. The hypertensive vascular changes reveal fibromyxoid intimal thickening and mild medial hypertrophy, which leads to thickening and narrowing of pulmonary arterioles [16]. True vasculitis and pulmonary hemorrhage are infrequent features of SyS [18]. Patients with SyS occasionally complain of esophageal motility disorder with gastrointestinal reflux; which leads to superimposed aspiration pneumonia [1,19].

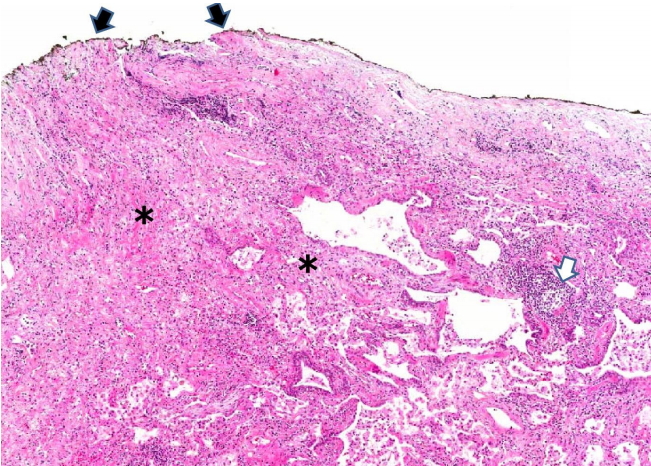

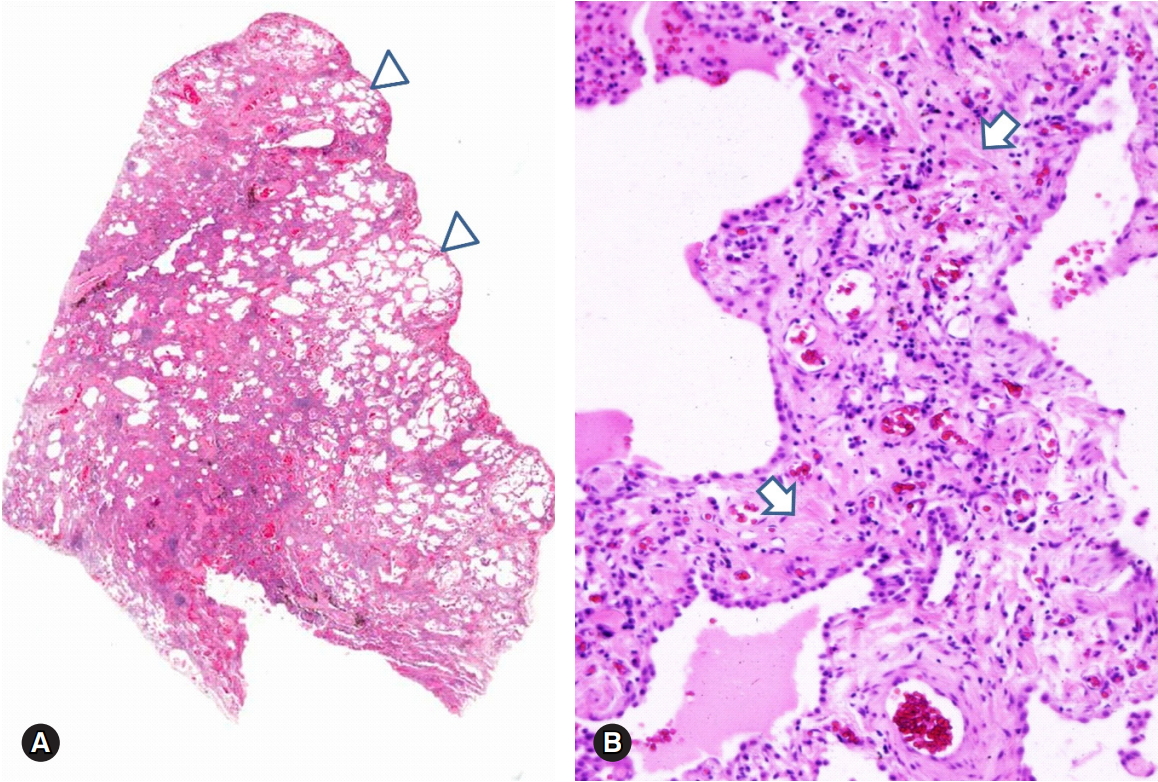

Histopathological pulmonary patterns in systemic lupus erythematosus

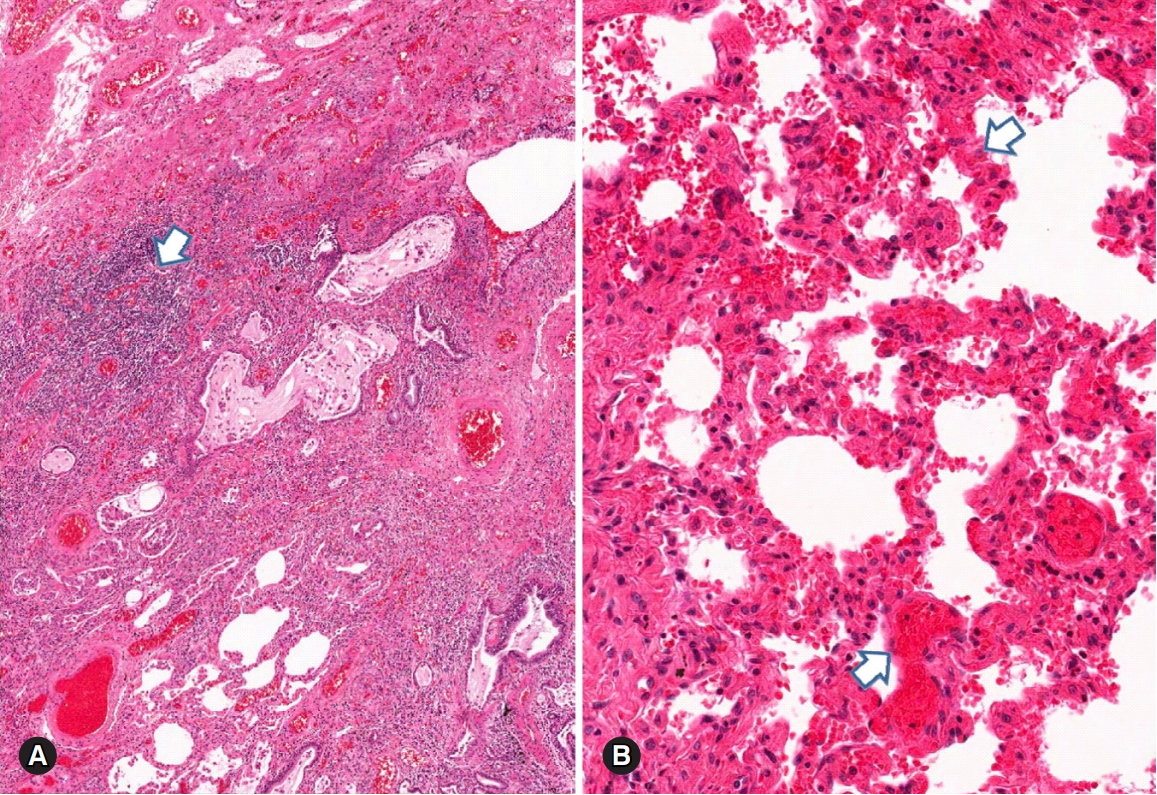

Pleuritis is the most common pleuropulmonary change of SLE, and microscopic features such as nonspecific pleural inflammation with fibrin deposition and fibrosis can be observed [20]. Cytological findings of the pleural fluid in SLE patients reveal characteristic lupus erythematosus cells consisting of neutrophils or macrophages with cytoplasmic degenerated nuclei [1]. Histologically, SLE reveals acute lupus pneumonitis with nonspecific acute and organizing lung injury patterns [21,22]. The most common microscopic features of SLE-LDs are acute and organizing DAD with fibrinoid microthrombi, hemorrhage, and focal hyaline membranes [1,21] (Fig. 4A). OP also can be a common finding in SLE [23] (Fig. 4B). Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) can be a fatal acute complication of SLE with capillary immune complex deposition. DAH reveals fresh hemorrhage or hemosiderin pigments in the alveolar spaces and alveolar septa, associated with or without capillaritis [1,24] (Fig. 5). Histological features of chronic lung disease are also observed in SLE patients. Mononuclear or lymphoplasmacytic cells are infiltrated in the interstitial and peribronchiolar areas, with variable cellularity of NSIP pattern but less prominent fibrosis [1,20,22]. Pulmonary vascular disease can occur in SLE by chronic thromboembolic disease or repeated vasculitis with healing [1]. The features of vascular disease show active vasculitis or chronic fibrous intimal thickening to plexiform lesions [1,2]. UIP, diffuse interstitial fibrosis with NSIP pattern, LIP, or amyloidosis are occasionally reported in the literature [2,5,25].

Lung parenchymal changes in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Histological patterns of organizing diffuse alveolar damage (A) and organizing pneumonia (arrows) (B) are present (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40 [A] and [B]).

Pulmonary parenchymal hemorrhage in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. (A) Diffuse parenchymal hemorrhage associated with lymphoid aggregates (arrow) and vascular congestion in the fibrotic interstitium. (B) Diffuse and fresh alveolar hemorrhage (arrows) with no distinct capillaritis (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40 [A] and ×100 [B]).

Histopathological pulmonary patterns in polymyositis and dermatomyositis

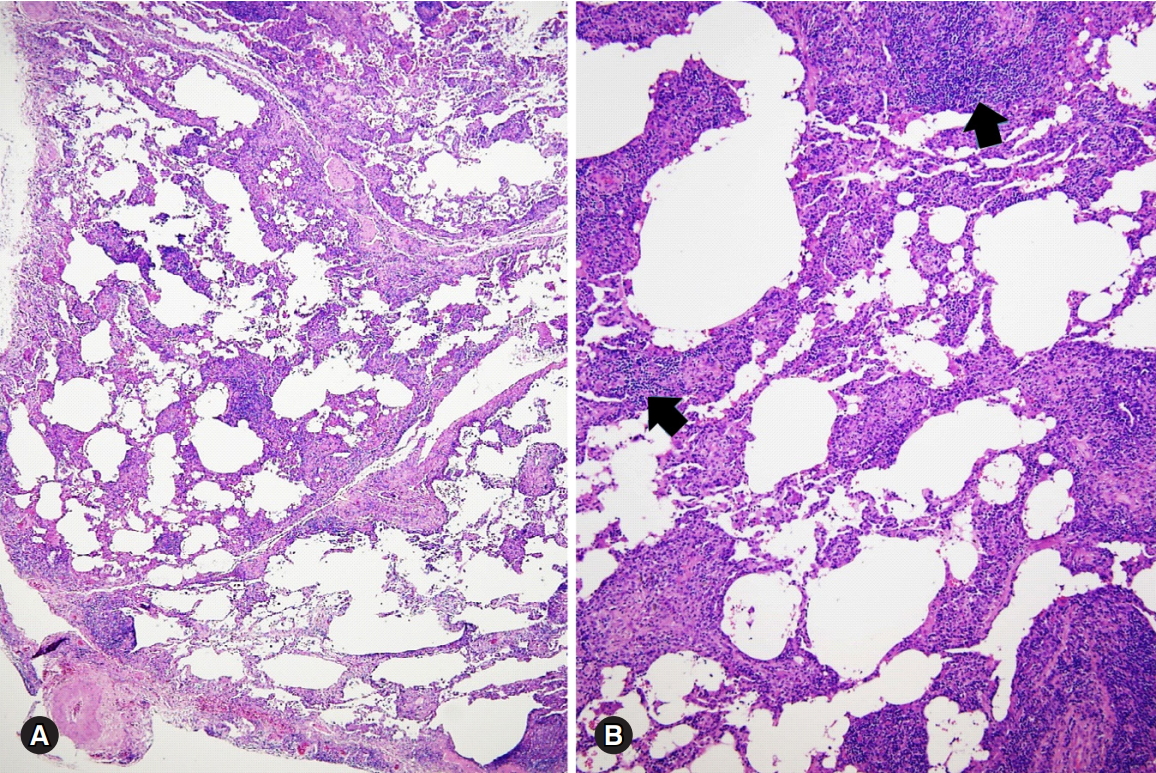

Chronic lung changes in PM-DM reveal diffuse interstitial pneumonias with cellular, mixed cellular and fibrotic or pure fibrotic NSIP patterns [1,2,26,27] (Fig. 6A). The OP pattern can be seen in PM-DM patients treated with steroid treatmen [28]. PM-DM shows UIP pattern, and the lesion contains abundant lymphoplasmacytic or mononuclear cell aggregates [2,11,28] (Fig. 6B). Patients with PM-DM occasionally show features related to DAD, which suggests an acute exacerbation of the underlying chronic lung disease and poor prognosis [1,27-29]. Occasionally patients with PM-DM reveal follicular bronchiolitis, LIP, DAH, pleuritis, airway involvement, and vasculitis [30].

Fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern in a patient with polymyositis (A). Usual interstitial pneumonia pattern is present in another lesion of the same patient (B). Diffuse interstitial fibrotic thickening associated with honeycombing (asterisk) and scattered lymphoid aggregates (arrows) are present (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×10 [A] and ×100 [B]).

Histopathological pulmonary patterns in Sjögren syndrome

Sjögren syndrome associated ILD (SjS-ILD) reveals various features of cellular NSIP pattern, follicular bronchiolitis, lymphoid interstitial hyperplasia, and LIP [1,31]. Common histological patterns of SjS-ILD are NSIP with cellular, fibrotic, or mixed patterns [32]. SjS-LIP shows florid peribronchiolar and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates with expansion to the alveolar septa (Fig. 7). The LIP lesion also reveals germinal centers, and occasionally non-necrotizing granulomas [1,33]. LIP is most frequently associated with SjS among CTD-LDs, and can be a precursor lesion of malignant lymphoma. About 25% of LIP patients have SjS [1,31,33]. SjS frequently shows involvement of the large and small airways, and the small airway reveals chronic bronchiolitis and follicular bronchiolitis with bronchiolocentric nodular lymphocytic infiltrates and reactive germinal centers [1,31,33]. CTD-ILDs and pleuritis are rare in SjS. Acute and subacute DAD patterns are seen in acute SjS-ILD exacerbation cases [31].

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia pattern in a patient with Sjögren syndrome. (A, B) Various degree of the interstitial thickening with abundant lymphoplasmacytic cells aggregates (arrows) is present (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40 [A] and ×100 [B]). Courtesy of Professor Jin-Haeng Chung, M.D., Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

Histopathological pulmonary patterns in mixed connective tissue disease

Histologically, MCTD patients show one or more specific CTD patterns [1,34]. MCTD patients frequently show acute fibrinous or chronic organizing pleuritis [34]. MCTD patients with acute exacerbations of underlying pulmonary disease reveal findings of OP or DAD [1,23]. MCTD patients with fibrotic NSIP or UIP patterns are rarely reported in the literature [35]. MCTD-LD frequently shows pulmonary vascular disease, and the vascular change is related to fatal pulmonary hypertension. Microscopic examination shows endothelial hyperplasia, intimal fibromyxoid hyperplasia, and medial muscular hypertrophy in the vascular structures of MCTD-LD. Advanced cases of MCTD-LD occasionally show plexiform arteriopathy [36]. Vascular changes are an isolated lung lesion or are associated with interstitial fibrosis [1,35,36].

Differential diagnosis of connective tissue disease-associated lung diseases

Histological findings of CTD-LDs can overlap with pulmonary manifestations of CTDs and various drug treatments which induce histological changes in the underlying lung diseases [1,8]. Differential diagnosis of CTD-ILDs includes UIP, NSIP, LIP, and OP patterns. Several CTD-ILDs showing these histological patterns should be considered as a differential diagnosis of non-CDT-ILDs. Viral infections can show cellular NSIP patterns, resolving phase of bacterial pneumonia can show an OP pattern, and fungal or mycobacterial infections reveal necrotizing granulomas morphologically similar to polyangiitis with granulomatosis [1,37]. Pulmonary toxicity induced by immunosuppressive drugs for CTD can cause lung injury patterns such as OP, cellular NSIP, DAD, and vasculitis [1,4,38]. Lung injury caused by inhalation or aspiration of toxic materials can cause bronchiolitis and bronchiectasis. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia sometimes requires a differential diagnosis with UIP and NSIP. Lymphoproliferative disorders in SjS-ILD are similar to cellular NSIP and LIP, and should be ruled out if the inflammatory infiltrate is florid [1,32,39]. Fibroblastic foci are diagnostic histological findings in idiopathic UIP, but it is absent or rarely seen in CTD-LDs. On the other hand, histological findings of prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates associated with lymphoid follicles are rare in idiopathic UIP or NSIP [14,40].

Conclusion

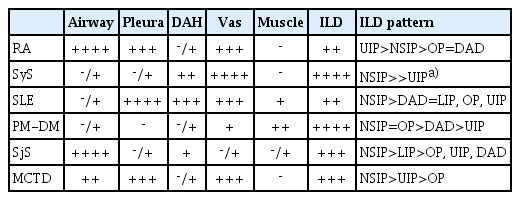

ILDs, large and small airway diseases, pleural and pulmonary vascular changes are common in CTD patients. Histological patterns of UIP, cellular and/or fibrotic NSIP, LIP, DAD, and OP can be seen in the lungs of patients with CTDs (Table 1). Pulmonary changes of CTDs can be caused by the direct involvement of the CTD in the lung by drug reactions from the patient’s medications, or by infections caused by autoimmune diseases and their related treatments. Clinical information and laboratory findings of patients with CTDs are important for the interpretation and accurate diagnosis of CTD-LDs in lung biopsy, and a multidisciplinary team with the participation of pathologists, clinicians and radiologists can do an accurate diagnosis of CTD-LDs.

Notes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.